Baseball was part of my boyhood experience, and I was blessed with the ability to continue competing in that sport throughout high school and college. Then I turned to coaching. In my lifetime I have taken thousands of swings with a bat. However, there were only two that broke windows and brought unexpected reactions.

The first of those swings followed a brief episode playing with a basketball in our front yard. Somehow I lost control of the basketball and was horrified to see it hit and crack one of our living-room windows. When the cost of replacing that window was determined, I didn’t see a penny of my allowance for the next five weeks.

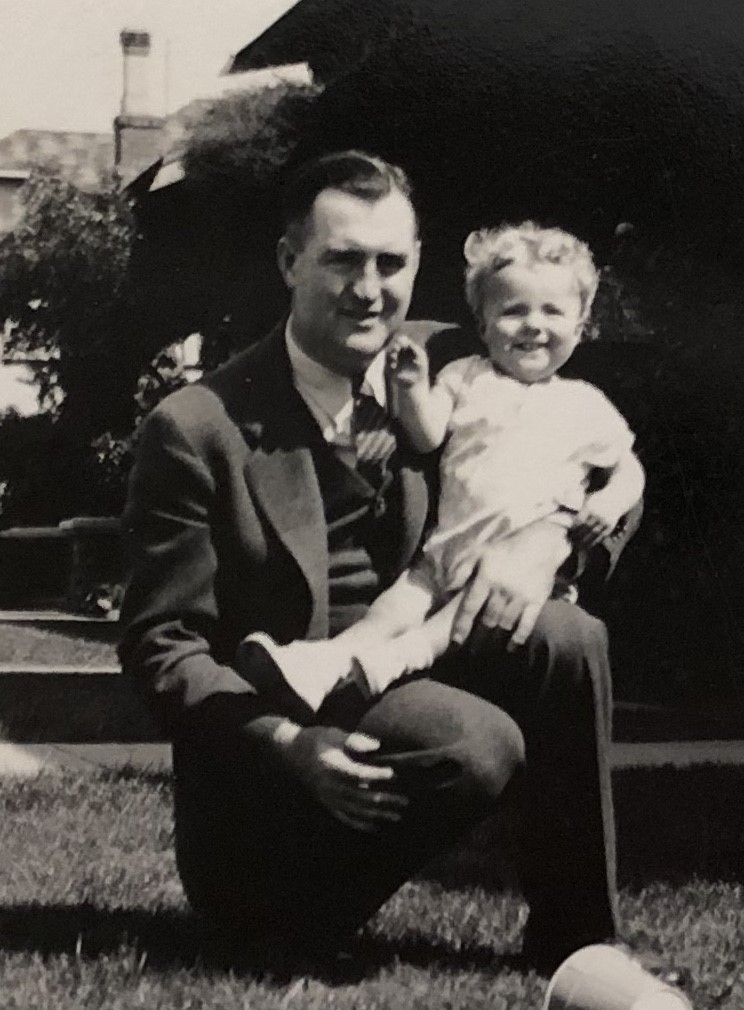

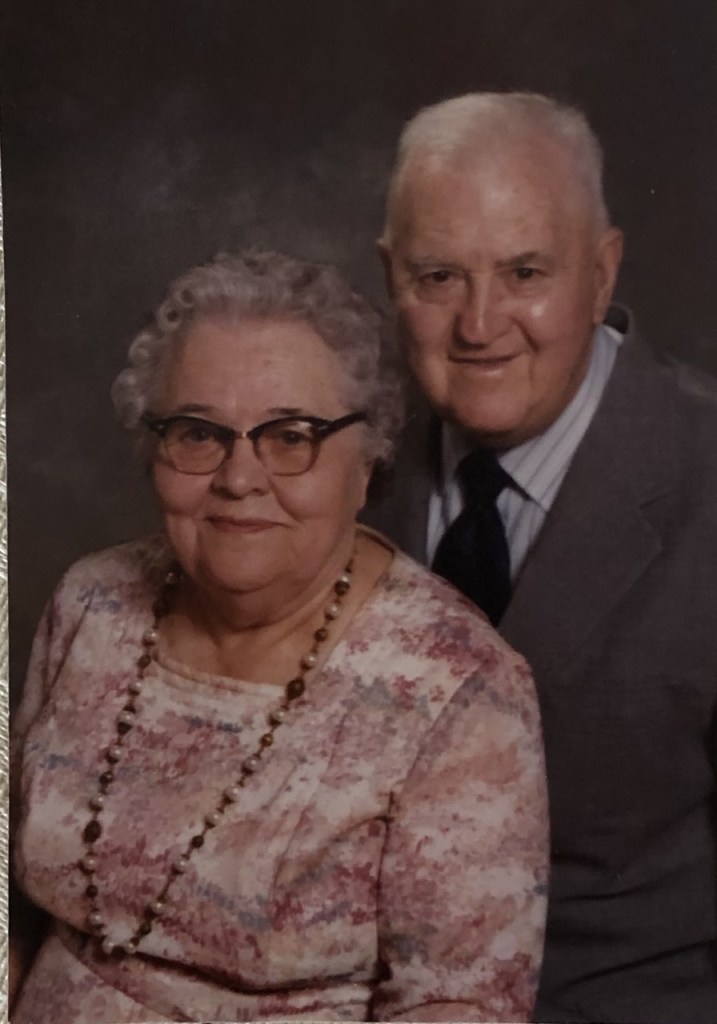

Soon baseball season arrived and again I was playing in the front yard, this time armed with a bat and ball. On one errant swing I fouled the ball off and heard the sickening crash of it going through a window—the same window as before. Again I trudged inside to face the music saying, “It looks as if I’ll be losing my allowance for five more weeks.” My dad replied, “No, you won’t. You already paid for that window. I had been putting off replacing it, but with that gaping hole through the middle I can no longer put it off.” My dad was sometimes tough, but always fair—at times surprisingly fair.

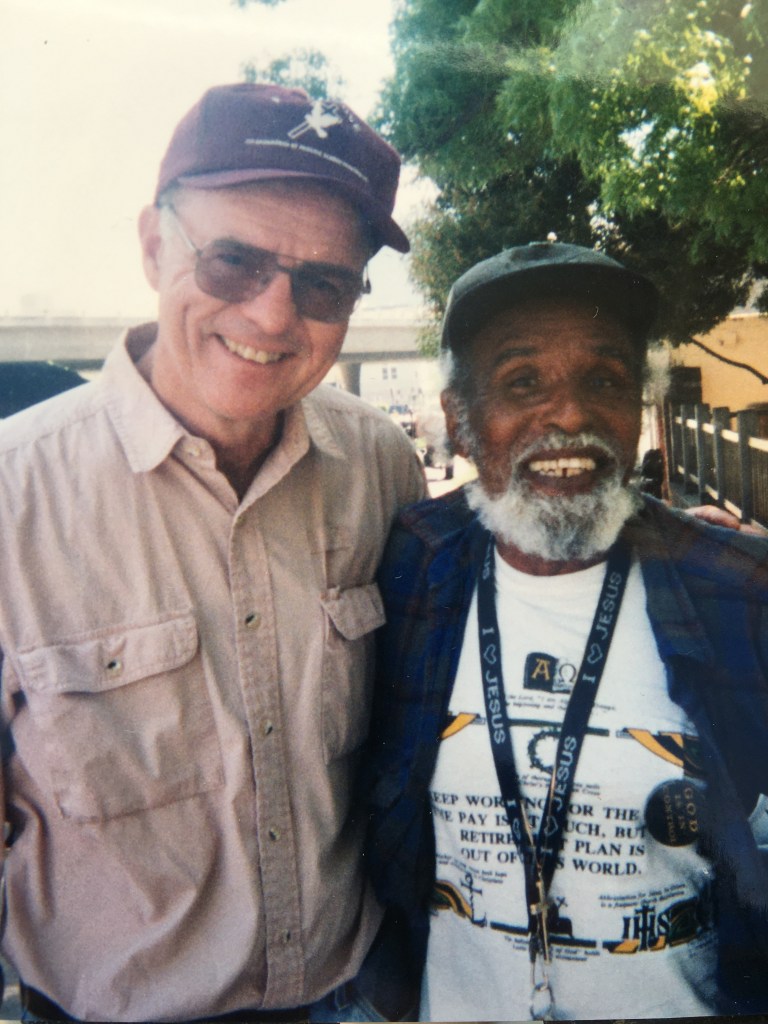

Years later, when sharing baseball stories with a young man I was mentoring, I was reminded of another swing—a long home run I had hit over the right field fence in Alameda’s Washington Park. There were other home runs, including a memorable one against U.S.C., but I believe this one was the longest ball I ever hit. I didn’t hit many home runs nor strike out much either because I was more of a contact rather than power hitter. If I saw a pitch coming over the inside of the plate, I got the bat out in front and pulled it. But if the pitch was coming over the outside of the plate, I simply went with it, driving the ball to the opposite field.

Anyway, on that day in Alameda, the pitcher threw me a change up that didn’t lose enough speed to be effective and stayed up in the strike zone as well. He couldn’t have given me a better pitch to hit, and I got all of my body into that swing. It sailed well over the fence and was later estimated to have landed 420 feet away. For me, that was as long as it got.

A few days later, we learned that a man living across the street from that park had called to find out who had hit the ball through his front window and broken a vase in his living room. Strangely he seemed happy about the whole thing. Then he explained, “I’ve been paying insurance on that window for 30 years and finally get to collect on it!” People are interesting.

This is not unlike life itself where sometimes we foul up and sometimes we come through—as if getting a timely hit. My dad always said, “If you have two strikes and the pitch is close, don’t risk going down with the bat on your shoulder.” So I believe we do well to grasp our opportunities by at least taking our best swings. And if someone nearby swings and strikes out, we have a different opportunity—to offer encouragement and try to lift someone’s spirit.